Home | Key Dates | Patuone - A Life | Whakapapa | Publications | Photographs & Paintings | Links | Glossary | Contact Us

Page 1 | [Page 2]

Whakapapa Fragments

In the administrator’s collection are fragments of tātai recorded on diverse pieces and sometimes fragments of paper in the 1880s and 1890s. Again, these are often extremely difficult to read. The connections will be clear to some readers from cited tātai earlier and their own knowledge. Some tātai are also repeated from earlier text to facilitate connections. What is apparent is that these tātai which relate to the administrator’s grandfather Okeroa, are mostly Te Parawhau with connections to others including Ngāi Tāhuhu and Patuharakeke. Where necessary, explanations are provided. Typically, there are some confusing aspects and contradictions and much more research is required. They are reproduced here for the first time to assist in further research and cross-referencing. Many of the names will be familiar to some and suggest significant tūpuna after whom various hapū were named. The use of ‘ta’ indicates ‘from’, ‘ko’ stands for ‘it is’ or in the sense here, ‘came’. The term ‘ka moe’ means ‘married’, ‘ka moe ia’, ‘he/she married’ and ‘ka moe a [name]’, [name] married’, referring back to the name immediately preceding:

Na te tuahine o Te Waha ko Hakurangi

(So the sister of Te Waha is Hakurangi). (Te Waha is Te Wahanui).Honetana he uri no Te Tuhinga no Ngāi Tāhuhu

(Honetana is a descendant of Te Tuhinga of Ngāi Tāhuhu)

( Details about the history of Ngāi Tāhuhu and their key hapū, Ngāti Rangi and Ngāti Tu, are provided in the text).

The following fragment relates to Hineamaru of Ngāti Hine:

Ko Wehu x ko Te Ngaro x ko Hineamaru

ko Pera x 1. ko Toruwera x Te Ringihanga

xxxxxx x 2. ko Rawa 1. Mangu

2. ko Taurikarika

3. ko Makaweuruko Mangu x Raewera

ko Uhinga x ko Taurere

xxxxxxx

1. ko Hauhau x Taupeka

2. ko Wheoro x ko Kupa

3. ko Te Huru x ko Whatonga

4. ko Pahara x ko Renata

5. ko Herekino x ko Te Hura

xxxxxxx

ko Wheoro x Te Raki

1. Taurawhero

2. Tara

3. WheTara

Kauhoea

Maihi Te Pua

Tohia

MotuWhe

Parehuia

ko Hikuwao

ko Karekota Hineamaru ko Pera

ta Pera ko Waipihangaarangi

ta Waipihangaarangi ko Whakautu

ta Whakautu ko Wheoro

ta Wheoro ko Taiakau

ka moe a Taiakau ia Te Puke

Hukohu Taraua Hare muri Okuoku muri ko Te Hounuita Taurahaiti ia Whareangiangi

ta Kauangarua ia Tarataraua

ko Te Karetu Pona ko Te Waikeri

Karetu ko Puta ko Mata

Ngorengore

Kauangarua ia Te Haara

Karetu ia Maara

Hotu (1) Maatai (2) Ngorengore

Hotu ia KorahaKo Houmia te matua, he tātai Parawhau

ko Roto te tuatahi i muri ko te Maru

ka moe a Roto ia Matai kia puta Te Pukohukohu

ta Te Maru ko Kahukura tana ko Toka, ka moe ia Pehi

na tetahi o nga wahine a Te Maru tana ko Te Umangawha

ta Te Umangawha ko PanapaHe tātai Hongātirihia tenei:

ka moe a Rehia ia

Irakau Taraua

ko Te Kaki ta Te Toko

ko Kahutaharua

ka moe ia Tauwhitu ki a puta

ko Teraratohora

ko Tohekainga

ta Teraratohora

ko Toko

ko Taranui

ka moe a Toko ia Hare

kia puta ko Te UrihekeNga uri o tenei hapū o Ngāti Moerewa ko Kuao.

Ko Rakeipaka te tupuna

tana ko Ngatokotoru

tana ko Tao i muri ko Maro [he wahine]

ka moe a Tao ia Rurairihau

Taraua

ko Kohinetau

i muri ko Mokonuiarangi

tana ko Te Mohi

tana tuarua ko Te Auru

tana Ritoutakaka moe a Kohinetau ia Maiwhiti

Taraua ko Taratikitiki

ona uri ko Heta Te Hara i muri ia

Taratikitiki ko Tetaitapu

ona uri o Tetaitapu ko

Te Kauwhata

he whanaunga Pene Taui

A further part of this whakapapa which is extremely difficult to read relates to Te Ponaharakeke:

Tamaro ko Te Makoko

tana ko Whari ka moe ia Te Ponaharakeke

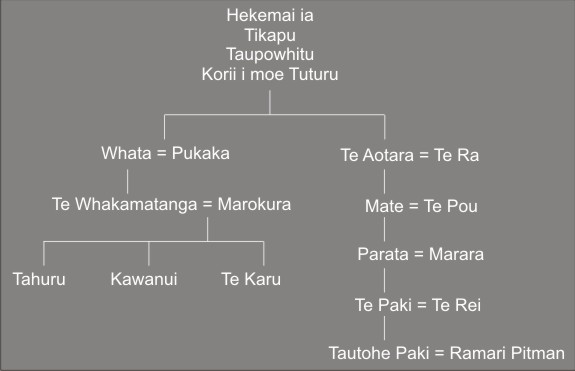

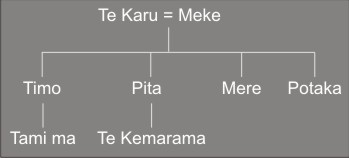

Another fragment details further Patuharakeke connections. The descendants of Tahuru, Kawanui and Te Karu appear below:

Tahuru = Kiha

Whatarangi = Tautapa

Te Paea = Pene Tahere

Raukura

Kawanui = Tunui

Puhirai = Haea

Rangiwahawaha

Further Linkages Between Ngapuhi and Tainui

These whakapapa are self-explanatory with key names from Ngāpuhi and Tainui being clear. The whakapapa here were handed on to the administrator by kaumatua:

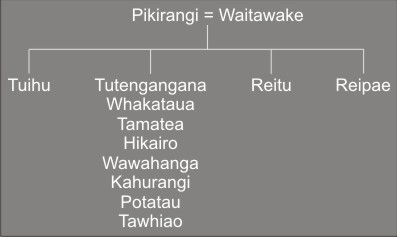

The sisters Reitu and Reipae while often couched in legend, were real people. The whakapapa trace from Hoturoa, captain of the Tainui. The Parents of Reitu and Reipae were Pikirangi and Waitawake:

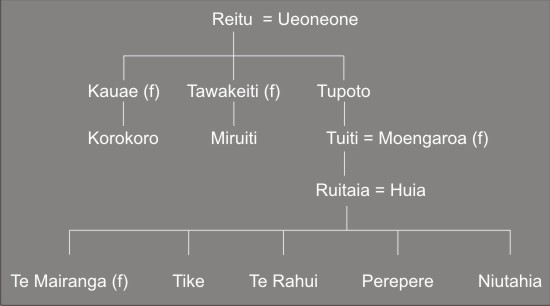

The whakapapa for Reitu in Ngāpuhi is:

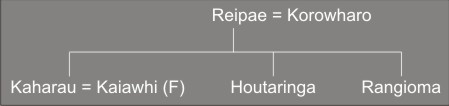

The whakapapa for Reipae is: 1

Other versions give the father of Reitu and Reipae as Wairere.

He Korero o Nehera (Historical Narratives):

These are also recorded in family archives. Other sources are also cited.

In a korero recorded in Māori by from testimony of Hori Rewi and Henare Te Pirihi in 1903, an extensive history related to details of the Whangarei, Takahiwai and Ruakaka areas emerges 2. This document provides a detailed explanation of the Ngāpuhi expansion towards Whangarei and of the highly complex circumstances and events associated with it. Within it also, bound up with the events of history are many whakapapa connections which are again rendered even more complex by multi-generational use of identical names. The account as translated is:

My account begins with the giving of this land after the conquest by Tawhiro. Waipu was given to Te Hakiki. I did not know the boundaries of Ruakaka. There was no gifting of that land. The gifting of that land, Ruakaka, was performed by Ngāi Tāhuhu when Pae married Te Kahore. After Pae made the gift to Te Kahore he received a request from Te Raraku at the time Tawhiro gifted [??]. No reply came via Tawhiro. The reason for this was his offspring granted Te Raraku (his request). Tawhiro gifted Rangiora to Pukerahi, Puhi and Motatau, the territory comprising Pukewherowhero, Puhangina-wai, Kauere Terake, Patuparehe, Te Whakatete, Tamarikirau. To the North down to Hirauta River he gave Maungatawhio (and?) Te Raparapa. Turning eastward (he gave): Mangawhati, Poupouwhenua and Te Koutu. Southward (he gave) Puke-wherowhero. That is the extent of the boundaries of Tawhiro’s allotments to Pukerahi, Puhi and Motatau.

They returned down (Northward) to the mountain. Motatau, Pukerahi and Puhi returned up here. They remained in that land (where addressee is). Motatau dwelt at Rangiora, where his pā was. Puhi’s pā was Te Kouparepahi, and Pukerahi’s pā was Ngātiti. At a certain time they turned [in] to Pukerahi’s pā at Ngātiti. They were spotted by Ngāi Tāhuhu on the side at the entrance of Whangarei harbour to the East, [so] it was known that Rangiora had been settled. Hikurangi sent a message to Wairau that Ngāi Tāhuhu were heading there. Their chief was Puakāka. When Hikurangi arrived in person, Ngāi Tāhuhu were crossing this way. They (Pukerahi, his younger brothers and their people) were living there at Ngātiti. When the war party was sighted outside Takahiwai, Pukerahi instructed that one of their own children be ritually killed, and when dead the heart be presented as a sacrifice to their gods so the latter would be favourably inclined toward them. When the war party arrived on the beach below Ngātiti, Pukerahi called for certain people to come out and show themselves. When they did, spears were thrown down at the war party. The spear throwers were made from kahikatoa.* When the spears impaled people, Puakāka called out: “Break them! May these calls rally forth to snap them [the spears] lest they wound people, and thus it was that Pukerahi’s declaration was heard: “A mere kindling fire will not set all aflame! May the shame spread across the land!” After that Puhi taunted, “Bring, bring Rangiora Te Kouparepahi, the house of Te Mānuka!” At that juncture Puakāka had edged very close and it was then that Motatau leapt upon him. Puakāka died and Ngāi Tāhuhu fled. That was the end of Ngāi Tāhuhu. Returning to that place, from the time of that battle at Ngātiti, calm settled there.

When Ngāi Tāhuhu fled, that child through his deed of sacrifice brought peace. After that, Te Taotahi married Te Ao-Hei-Awa. Mangawhati was gifted by Pukerahi, Puhi and Motatau as a dowry for Te Ao-Hei-Awa. Then Maketu married Te Hei-Raukawa, and Te Whakaariki gave Te [Wita??] as a dowry for Te Hei-Raukawa. After it was given, Te Koiwi lived there. After that came the battle of Ngāti Maru and Te Taoū at Mangawhati. The tribe of Te Koiwi sprang from that endowment to Te-Hei-Raukawa and some of those people died there at that battle. Te Kawana was the chief at the time of that battle. The house, Te Kapaha, was occupied by Ngāti Tū-Te-Whare, Taringa-roa and Motu Takupu. It was a house of pain for Te Rangi Tuoro who died in the battle at the hand of Moti Takupu during the pursuit to Mangawhati. It was Maketu who achieved peace. Maketu spoke thus: “Those who died at that place died again. The living lived again. Let a remnant escape of whoever fled from there. The patu of Te Katipa Te Awakeri lives on”. The pathway was cleared by Maketu. Te Huru-ki-runga was covered over. The peace achieved through that fight was sustained. Ngāti Maru and Te Taoū returned home permanently. The descendants of Pukerahi, Puhi, Motatau and Koiwi remain on the land being discussed, namely this block. After that Poupouwhenua was ceded by Te Pirihi and Mate for their plunder at Matakana. Following this, Te Karakaho was given over by Te Pirihi and Te Rangiwhiuwhiua to Te Poihipi. In this place Tamumu became extinct. Since then that place has been called Ngaro-Tamumu. Te Pirihi thought that Hona would not participate if his group entered a conjoint claim for income derived from places within these districts under discussion. He said that Weku and Hona should make application for Kopua-wai-waha, Te Whakatete and Te Wai-o-Rehua and take the income of these places lest Hona be wronged by the descendants of Pukerahi, Puhi and Motatau. The boundary was established to demarcate that area from this side to the southwest. That kindness to Weku should end there. After that came Te Rata Pou, a descendant of Pou, who begged Te Pirihi for Te Mata, so he could sell it. Te Pirihi agreed, and it was Te Rata who partitioned and sold Te Mata out of this block. Te Pirihi’s regard for Te Rata Pou ran out. Do not substitute the descendants of Motatau for Kopua-wai-waha who descended from Wēku, that is the offspring of Te Koukou and those of Nehe Tuaru, and ultimately Hona. The reason for this was Te Pirihi’s fear that Hona would be ousted by Motatau’s descendants, Pukerahi’s people. Puhi’s weren’t involved. That was the reason they did not live there continuously after this, because of that money. Following that the term of Te Pirihi’s binding decision expired. This block and Mangawhati were leased by Wiki Pirihi. The judgement on Mangawhati was that it was leased jointly to Hone Henare, and that portion was administered by Te Pirihi. Te Ao-Hei-Awa was the ancestor and the people within it were the second Te Korehu and Te Rēweti. Hona saw the judgment on that land and did not put up a claim for that land until these things I am discussing were actioned by Te Pirihi at their place which was decided upon as Te-Wai-o-Rehua, Te Whakatete and Kopua-wai-waho. Hona had assumed the parts from this side of Rangiora, the side toward Whangārei. He would not come to these ones I’m speaking of, those sold, given up and let, and Te Pirihi’s leases up until the judgement on Mangawhati. Hona did not object until Wiki leased this block to Hone Henare. After that, Rangiora was appealed by Wiki against Hori Nuku Meha. When the policeman arrived to convey the statement, Hori Nuku Meha came here. The reason he came here was so that Hona would be lenient in his judgement. Hona didn’t present himself at court. Do not respond to that plea. Accordingly the court did not agree that Hori Nuku Meha be ordered to pay settlement of that grievance. It was I myself currently addressing you, who instructed Te Pirihi that afterwards he was to deal with Wiki as he saw fit.

* Kahikatoa - red-flowered Mānuka.

Apart from the intrinsic interest in the historical details provided, the ritualistic killing of one of the children under the instructions of Pukerahi also provides an insight into old practices related to the propitiation of the gods.Beyond this, the key questions which arise from this account relate to its concordance with other accounts both from the point of view of the related events and the supporting whakapapa. Te Kahore married two sisters, Pai and Weku who through their mother Pare came from the Ngāti Rongo hapū of Ngāti Whātua. Another explanation of this is in the administrator’s whakapapa and archive collection also dating from c.1896: the verbatim text, illustrating points made about the challenges of dealing with many of these old manuscripts is:

E rua nga mea matau nei ahau Ko te tātai tangata Ko te tātai whenua. Ko te tātai tangata nei. Ta te Ahitapu ko Te Rarau Kara Tana ko Te Houmuri ko Papatikoreti. Ka puta Mahanga mai. Ko Te Waha ko Te Hawato. Ka moe a Te Waha ia Pare no Ngāti Whātua tenei wahine. Ka puta ki waho ko Te Raraku. Ka haere a Te Raraku ki nga Tuahine kia Pae raua ko Weku tae mai i roto i Ngāti Whātua. Koia ito raua i haere atu ai kia raua e noho ana hoki a Te Kahore ka homai Te Ruakaka. E kore hoki raua e homai Ihirauta ito Ngāti Moeroa kainga ki to Ngāti Whakapae ahi ka tika ano ta raua homai i te whenua o to raua matua tane o Hikurangi ki to raua tungane ki Te Raraku na ena wahine nei i tuku mai te whenua no Ngāpuhi ka hoki a Te Kahore.

(There are two things of importance: the genealogy relating to people and the genealogy relating to land. This concerns the genealogy relating to people. From Te Ahitapu came Te Rarau Kara. From him came Te Houmuri and Papatikoreti. Then came Mahanga followed by Te Waho and Te Hawato. Te Waha married Pare; this woman was from Ngāti Whātua. Te Raraku was born. After Te Raraku came the sisters Pae and Weku from Ngāti Whātua. These sisters married Te Kahore and gave him Ruakaka. They did not also give Ihirauta of Ngāti Moeroa to Ngāti Whakapae and it is again true that they maintained rights of occupation through their gifting of lands of their father Hikurangi to their brother Te Raraku and it is thus through these women that the land of Ngāpuhi came back through Te Kahore).

The point made here is that Pae (sometimes written Pai) and Weku married Te Kahore, the son of Te Ponaharekeke. Hikurangi is the Ngāti Tu rangatira Hikurangi who was to suffer great loss at the hands of Ngāpuhi. It was through Pae and Weku’s marriage to Te Kahore which brought about the gifting of rights to Te Ruakaka to their older brother, Te Raraku.

Te Karere Vol. 3 No.6, 1863 contains a very interesting article on testimony from what are clearly land claim hearings related to Te Roroa and factions of Ngāpuhi associated with Te Ponaharakeke, Kūkupa and Te Tirarau. The most significant details, apart from the various events and persons mentioned are the clear accusations of falsity and manipulation in whakapapa:

This land Mangakahia was given to Tewha, son of Te Waikeri and to his sister Kirimangeo; Whatitiri, was given to Te Kahore, the son of Te Ponaharakeke. Waikeri was the elder brother of Te Ponaharakeke. Hear then O Council, to our ancestors who lived on the land at Mangakahia, Wairua, Whatitiri, Whangarei, Tangihua: there they are buried on these lands. These are the sacred places, Te Angiangi, Te Rotokauae, Pukeatua, Te Ngawha, Te Waehaupapa, Tohanui, Pukanakana, Ruarangi Parahirahi, Haukapua, Oroarae, Te Motumotu, Rangikapohia, Haruru, Uruwhao, Hikurangi, this is the sacred place where the remains of Kūkupa were laid with those of former generations. Our Ancestors never saw the Ancestors of Te Hira, or of Matiu Te Aranui placed in those sacred places; even down to ourselves we, have never seen, known, or heard of such a thing. Therefore we hold fast to the land, no man can move us off what, though the winds blow and all their fury be expended on it. This house shall not be destroyed, for ever and ever, Amen.

Netana Taramauroa: The point that shall remark upon is the mention of my name in the papers submitted by Ngāpuhi in reference to the lineal descent, for they have named my father Ripa among their ancestors. I have understanding in this matter, for I am aged, when my father died I heard his words, I did not know the sayings of Ngāpuhi, the words they have just spoken. Who would suppose that Ngāpuhi would undertake to trace my genealogy? I am acquainted with the history of my own ancestors. It is not right that I should be dragged (by them) into evil, that is to say be mixed up with untruthful words. I say that this kind of counting up of ancestors is wrong. I did not hear of it formerly. If I had heard that, I should be living with Taupuhi at the present time (I should not be so much surprised); I say that these genealogical summaries are most untruthful. The tracing of my father upon his own lands in reference to the line of ancestors, these lands being Kiriopa, Te Whakatipi, Kaikohe, Te Tuhuna. Let the genealogy be set up in reference to these lands, for my father was the only man who thoroughly understood the enumeration of these ancestors, my father Ripa. In his days, and during the time of his keeping an account of the ancestors, no evil befell men (the parties concerned in this matter) even up to his death. When his descendants grew up they sought to obtain knowledge in their own way; evil, therefore, has befallen men. I am the only Ngāpuhi man residing among this people (i.e. the people of Te Tirarau) at the time I came (to Kaipara) it was not by friendship, but I came to the Europeans, and so I then saw these lands on the Wairoa. On my arrival there, I saw Te Tirarau only, in possession of his lands. There was no evil then among them, for there were no men at that time to disturb them. After I left (the North) they (Ngāpuhi) sought to create evil, that is to say, a plan was formed to take possession of the lands of these persons (i.e. Tirarau and party) of Te Tirarau and Hori Kingi. According to the best of my knowledge, they are living by right upon their own lands, and they both are speaking truth as are also all their party, or tribe. But the Ngāpuhi are false enough to attempt to take their, Tirarau's, land: this is wrong, I do not understand it. Let me end here.

Hori Kingi Tahua: This is the cause of them getting possession of Mangakahia, namely my dog skin mat. The cause of my obtaining Whatitiri was this, the rescue of the Ngāitāhuhu by Te Kahore. These are the grounds upon which I retain possession of this land. This is all I have to say; my paper which is now handed in will supplement what I have said.

Wiki Te Pirihi, father of Henare, also went on the title of Hurapaki at Kamo in the 1860s and this suggests a strong whakapapa connection to that land which consequently allowed him title with others. The name of the area, Kamo, now part of greater Whangarei, probably derives from settlement in the area by Motatau and Te Kamo.

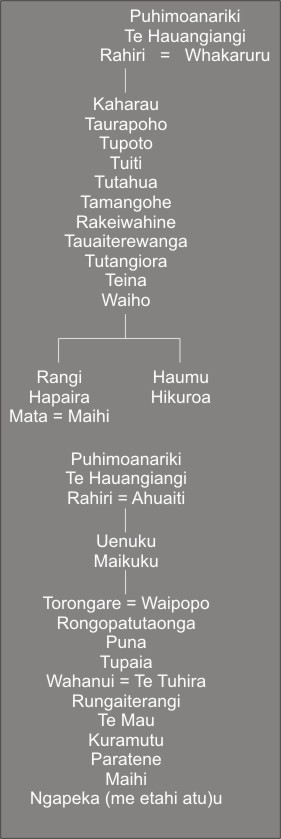

Ngāi Tāhuhu 3 were the tangatawhenua of the Whangarei area whose original territory spread from the Kaipara towards Ohaeawai and encompassed the extensively settled and cultivated Whangarei area including what today is the Regent-Kensington area, Mair Town, Whau Valley and the associated swamps, rivers and streams which provided an abundance of natural food such as tuna and kewai, and rich, fertile land for extensive cultivations. The prominent pā at Parihaka and the kainga Tawatawhiti were part of this extensive settlement as were other pā on both sides of the Whangarei harbour. Due to increasing pressure from the north the two principal hapū of Ngāi Tāhuhu (Ngāti Tu and Ngāti Rangi) found it more difficult to resist the confederated Ngāpuhi expansion southwards. Interestingly, however, the Hori Rewi testimony states that Ngāti Tu were part of the move against Ngāi Tāhuhu, the iwi grouping of which they were a hapū. Potentially this is a curiosity until one remembers that closely-linked groupings were often involved in major confrontations and disputations. Hikurangi, the rangatira of Ngāti Tu had a sister called Mihiao and through her husband Te Uiho from Ngāpuhi and son Ngarokiteuru, was instrumental in aiding and abetting this pressure from the north. Within this fact of collusion is contained the hint of treachery. Ngāti Tu were invaded by taua under the leadership of Wahanui 4 and Tawhiro who were half-brothers of Te Ponaharakeke of Ngāti Ruangāio whose base was Mangakahia. Subsequently, Ngarokiteuru took over much of the land from Tamaterau north, including the large and prominent pā at Parihaka 5. Tawhiro was eventually to be killed by Ngāti Maru on one of their raids north. This was at the battle of Otaika-timu fought in the environs of his pa Motukiwi, Tapu Point in the late 1790s.

As did Ngāti Ruangāio, the Ngāti Kahu hapū of Ngaroiteuru traced descent from Torongare, a significant rangatira descended from Rahiri through Ahuaiti, Rahiri's first wife and his first-born son, Uenuku. Torongare’s marriage to Hauhaua produced Hineamaru (founding tūpuna of Ngāti Hine) as well as Te Aongaua 6 and Tamangana. Ruangāio came from the marriage of Tamangana and Te Rangiheketini whose children were Tahora, Waihoa, Tikapu and Taurahaiti. Taurahaiti’s marriage to Waiharoto produced Teawhi (who married Te Hakiki) and Tawhiro. Taurahaiti’s marriage to Whareangiangi produced Kauangarua, Te Waikeri and Te Ponaharakeke 7.

As indicated previously also, Torongare, who has a strong association with the Whangarei area and who had a pā at Toetoe, is a rangatira from whom significant connections also descended to Ngāti Pāoa and the Kahui Ariki of Tainui. In fact, the Ngāti Pāoa chief Te Haupa, who was killed fighting in a taua to Te Tai Rawhiti with Patuone, Nene and Hongi Hika, was connected to Ngāpuhi through this strong Torongare and Maikuku line. Part of the reason why Patuone married Takarangi, sister of Te Kupenga of Ngāti Pāoa 8 as his third wife, was to settle old scores between Ngāpuhi and the Hauraki for good. Tawhiao Te Wherowhero had a wife, Hera, from the Torongare line so this is why Tainui and Ngāpuhi have an important link and why Koroki and Te Puea Herangi held and observed a special connection to Tai Tokerau: Hera was their tūpuna.

By the early 1800s, the Ngāpuhi ascendancy was complete with all the land controlled by various interlinked hapū of Ngāpuhi. Te Parawhau was the strongest under the leadership of a grandson of Te Ponaharakeke, Kūkupa, who also descended from Te Tokaitāwhio a major chieftainess of Ngāti Ruangāio. Kūkupa married Tahora, daughter of Ruangāio and Te-Ika-a-te-Awa. The administrator’s tātai show that in addition to Tahora, (a tūpuna of the administrator’s grandfather Okeroa Pitman) other children from the union of Ruangāio and Te-Ika-a-te-Awa were Waihoa, Tikapu and Taurahaiti. Kūkupa’s other wives were Whitiao, Taupaki and Te Hauauru. In relation to Tahora, some key tātai are:

Tahora

tana ko Te Putōtara

tana ko Wairoro

tana Tuihau

tana ko Te Haro

tana ko Ani Tauwhitu

tana ko Okeroa Pitmantana ko Te Putōtara

tana ko Uru

tana ko Ngawhau

tana ko Taoho

The Tauwhitu referred to in the following tātai, is not the same Tauwhitu from whom the administrator’s grandfather Okeroa descends:

He tātai Hongātirihia

Ka moe a Rehia ia

Irakau Taraua

Ko Te Kaki ta Te Toko

Ko Kahutaharua

Ka moe ia Tauwhitu kia ?

Ko Terara Tohora

Ko Tohekainga

Ta Terara Tohora

Ko Toko

Ko Taranui

Ka moe a Toko ia Hare

Kia puta ko Te Uriheke

me etahi ano

A tātai taotahi for Whitiao indicates connections back to Tāhuhunuiarangi the founding tūpuna of Ngāi Tāhuhu:

Tāhuhunuiarangi

Tāhuhupeka

Tāhuhupotiki

Te Ao-matangi

Rongomate

Tuangiangi

Te Ngāio

Te Hata

Wai-ihu-rangi

Waimererangi

Whitiao = Kūkupa

Kūkupa's pā was near Toetoe and the Otaika River on the Whangarei Harbour. Uriroroi was another hapū connected with Kūkupa. Kūkupa's marriage to Whitiao produced his sons, Te Ihi and Te Tirarau. Their half-sister Tāwera (from Kūkupa's marriage to Taupaki) married Parore Te Awha and this was all part of the consolidation of power and control by the wider Ngāpuhi alliance. Parore Te Awha, through his father Toretumua Te Awha also descended from the Te Roroa rangatira, Toa and therefore had connections to Ngāti Whātua as well. He was a grandson of Taramainuku from the Te Kuihi hapū and his mother, Pēhirangi descended from Te Whakaaria of Ngāti Tawake and Ngāti Tautahi. The connections here with Patuone and Hongi through a key line from Rahiri are also clear.

Te Ihi was particularly illustrious and for his prowess was named Te-Mana-o-Ngāpuhi. But, he died comparatively young at which point, Te Tirarau became the arikinui of the extended Whangarei/Te Wairoa territories. He figures highly in many reports related to the Whangarei area and territories to the south and west.

The killing of Te Taotahi c.1775 by Te Parawhau gave rise to the name of the hapū Patuharakeke which is associated with the southern shore of the Whangarei Harbour and centred upon Takahiwai 9. Certainly, the name Takahiwai itself 10 related to an earlier battle where the body of a rangatira was hidden under water for later retrieval so that it would not burden those warriors still able to fight and would remain undetected by the enemy and thus free from violation and desecration. The name Patuharakeke clearly indicates that Te Taotahi’s death occured in a harakeke patch, much as Patuone was named after a tūpuna killed by on a beach (one). One account suggests that it was Pokaia and his wife Turiwera who killed Te Taotahi 11.

The administrator’s cited tātai indicate that Te Taotahi married Te Ao-Hei-Awa and the issue were named Nehe (after his grandfather), Whakaariki, Te Korehu and Te Oneho 12. The Henare Pirihi korero describes Te Taotahi as having a brother Koukou and another sibling, Tai Haruru. There is scant reference evident other than the names 13.

Of course, as indicated in earlier discussion there were reasons why specific people were left out of detailed or specific whakapapa so perceived gaps may be a case in point. There is also the issue of selective identification and association in order to establish beneficial connections as well as the repetitive use of certain names and the use of multiple names, all of which confuses.

A block called Poupouwhenua was, however, ceded to the Crown in 1844 by Mate, Parihoro and Koukou. Henare Pirihi in his korero says that Poupouwhenua was given by Pirihi to the Crown for the ‘Matakana trouble’ which may have been a reference to a major issue in 1842 when Te Tirarau committed muru upon land at Mangawhare, at that point in possession of Thomas Forsaith who was a trader and later-to-be, protectorate official and co-editor with Dr Edward Shortland and George Clarke of the newspaper ‘Te Karere o Niu Tireni’ 14. The basis of the muru was an alleged desecration of a wahi tapu on the land concerned. Curiously, Governor Hobson instructed Protector George Clarke to seek compensation, following referral to the Colonial Secretary in London. Subsequently, Te Tirarau ceded 6000 acres at Te Kopuru to the Crown as compensation. Of itself, this transaction is curious and the response to muru committed for a perfectly legitimate reason, even more so. It perhaps reflects the earlier post-Treaty days where there was uncertainty and 6000 acres was of little consequence in the overall acreage of land under Te Tirarau’s chiefly control and discretionary powers of their disposal.

Other old documents in the administrator’s family collection dating from the 1890s detail various transactions related to land at both Takahiwai and another matter brought before the Court in relation Whatitiri by Taurau on 13 November 1896. This includes a summary of monies collected from a diverse group of Māori who were supporting the ‘Taurau application’. A total of £9/3/- was collected for what was clearly a case brought before the Court over ownership determinations arising from the complexities of initial settlement and subsequent raupatu of the entire Whangarei territories into their widest reaches 15.

Whatitiri refers specifically to the various interests and history arising from the ousting of Hikurangi the rangatira by Ngāpuhi. In the investigation of the Whatitiri block involving 21,362 acres, in 1894, Te Rata Rimi put forward a claim on behalf of Ngāi Tāhuhu who were then known as Te Maungaunga (The Remnants). He stated that the hapū present when part of the block was gifted to Te Uriroroi were Te Parawhau, Te Patuharakeke, and Te Tāwera, and they made no objection. He claimed that Parawhau and Te Uriroroi were beaten in battle and fled to Whatatiri, and that Hautakere was killed by Ngāti Whātua, and Te Ponaharakeke, Waikeri and Te Tirarau were killed by Ngāti Wai 16.

The entire and wider Whangarei area, given its great resources and having been so subject to upheaval related to war and conquest, ended up providing many complicated matters for the relevant authorities to consider with claimants seeking to establish rights variously through descent, inter-marriage or through raupatu and occupation. Added to the mix were sales to pākēhā.

A letter written in draft on behalf of a group of owners gathered at Waiomio and directed to Wiki Te Pirihi is dated 16 June 1896 gives instructions to Wiki Te Pirihi in relation to what was the Papatupu block at Takahiwai: the Peka referred to was a daughter of Te Keepa 17. Translated, the letter reads:

Waiomio, 16 June 1896

To Wiki Te Pirihi, Greetings,

In addition to our concerns about Peka’s survey application for Takahiwai it is also our absolute wish that the survey not intrude upon the Papatupu land which remains in our possession. We advise you that it is fine to arrange things in relation to your property and land. If the land is leased to pākehā and the timber allocated to them, remember to give up the same portion to Peka and those on her side in addition to those of you on your side rightfully occupying the land. Therefore you should detail those people and all property upon the land and also try to set aside the negative things arising from this process and also not allow the survey to ignore the decision and the section of the Treaty of Waitangi. Thus one quarter is for Peka and three quarters for you. Therefore we say to you that if the land is leased to pākehā; if the timber is sold to the pākehā, let this be between you and Peka. Arrange between you to take possession of the money and divide it between you keeping three quarters for those people on your side and one quarter for Peka and her side. This letter has been sent to:

Wiki Te Pirihi

Iraia Kuao

Henare Hemoiti

Hohepa Whitirua

Iehu Te Tuhi

Rawiri Te Ruu

Pirei Teiro

Hoane Tana

Werohia Haehae

Wiremu Weweka

Hira Mai Motukokako

Kereama Tauehe

The draft is in the administrator’s family collection although the identity of the administrator of the letter is not clear. Certainly it was clearly the result of a meeting at Waiomio, interesting in itself since after the Kawiti and Heke offensive against the government, Waiomio became a strong focal point for many such critical meetings and internal healing processes. One of the especially significant details is that relating to the mention of the relevant ‘section of the Treaty of Waitangi’. In this regard, it is clearly a contemporary of the ‘Ruri mo te Hui o Waiomio’ referred to later in the text and was part of an overall and final reconciliation (at least, to the extent possible) between the Kawiti and Heke factions and those of Ngāpuhi who had opposed them, including Patuone and Nene.

Together with Tauwhitu, Te Pirihi and his descendants were connected directly back to Nehe and Motatau and the significance of the Waiomio meetings becomes clearer with an intention of reconciliation and focus upon matters in common through conjoint support of various acitivities based at Waitangi and Te Tii. Patuone’s son Hohaia was involved in overall reconciliation with Maihi P. Kawiti and others on a wider front as well but it was these strong Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Manu connections with Patuharakeke and Te Parawhau which were the real keys to final reconciliation. Assertion of kinship links became critical, especially within the context of political events driven by the New Zealand government whose self-condoned actions ensured that generalised Māori loss and disadvantage continued. Thus the many and various meetings at Waiomio had much to do with discussions and actions throughout the 1880s and 1890s to seek redress for the actions of the New Zealand government in all its guises in relation to the treatment of Māori generally; the endlessly vexed matter of the Treaty and the ways it had been abused, and the continuing refusal of the British government in all its parts to play any meaningful role in the pursuit by Māori of justice. In spite of petitions to London by Māori, British arrogance and insistence upon process and protocol effectively placed Māori into a revolving room with many doors. Both the New Zealand and British governments had effectively mastered the art of obfuscation, denial and conjoint inaction and any meaningful way of moving forward was not considered. Even without overt collusion, their insulting treatment of Māori continued as resentment and anger of Māori collectively also grew. It is likely that the assumption of inevitable Māori extinction, given time, can explain the motives of the New Zealand and British governments: they hoped for a solution through the key players, agitators and interests simply dying out. Unfortunately for them, Māori proved to be far more resilient than imagined and this created a new dynamic which then had to be reckoned into things. The predictions and confidence of tūpuna would have their day eventually.

Another significant outcome, apart from petitions and efforts to establish meaningful Māori parliamentary autonomy and co-operative Kotahitanga actions was the assertion of a spiritual renewal through ‘spiritual leaders’ such as Ani Kaaro and Maria Pangari who generated considerable concern on the part of pākēhā officials 18. These events clearly arose from frustration at lack of any progress with successive New Zealand governments and a constant failure to obtain either acceptance of or satisfaction with grievances arising from the endless abuse of the Treaty. The fact of Ani Kaaro assuming what were effectively tohunga rights is of itself interesting. Apart from the mana of Ripia, Patuone’s grandmother, the mana of Tapua had also passed to Patuone and then, by virtue of his status as the senior surviving issue of Patuone, to Hohaia. Hohaia, however, appears to have lived somewhat within the shadow of his father, Patuone and uncle, Nene. Thereafter, Ani Kaaro apparently assumed the rights by virtue of birth and probably as a result of certain tohu, although the children of Hohaia in order of seniority were Patuone, who married Mere Pumipi; Te Tawaka, who married Eru Nehua; Hoana, the administrator’s grandmother who married Okeroa Pitman; Raupia, who married Hohepa Heperi; Ani Kaaro, who married Ngakete Hapeta; Kaioha (Kaiaho) who married Toki and Raunatiri who married Taati Pairama. Within family dynamics, there were thus some interesting moves taking place and on the part of Ani Kaaro, some vigorous self-promotion and allied sponsorship of others as a tohunga matakite. The fact of her effectively ‘living apart’ within the family perhaps explains much as is the fact of her having no issue. In Māori terms, the production of no issue usually signifies that a person has another critical role related to another important area of practice or production which cannot be contaminated by procreation. The role of continuance of the family line thus falls to others. Because she was ‘confined’ deliberately in later life and after consideration of the evidence, it is the administrator’s belief that Ani Kaaro’s role as a spiritual guardian within the family was clear. At many events and hui, she was often the only woman present 19.

Waiata:These waiata are songs and poetry recorded in family archives. In many cases they are very old.

< < Back to Whakapapa [Page 1]

_______________________________

1. This tātai is taken from Jones and Biggs Nga Iwi o Tainui (1996). The indication of a marriage between Kaiawhi and Kaharau is not supported by other tātai known to the administrator. Indeed, within sources, the tātai related to Reipae in particular are divergent. Over time, these details will be clarified. (back)

2. This handwritten document is in the administrator’s family archives and extracts are used to detail specific points in this section. (back)

3. The founding tupuna of Ngāi Tāhuhu was Tāhuhunui-o-rangi, an ancestor of Rahiri’s first wife Ahuaiti. Uenuku’s wife Kareariki was also a descendant of Tāhuhunui-o-rangi. (back)

4. Wahanui is often referred to simply as Waha or Te Waha. (back)

5. This was, in its time, the largest inhabited pa in the entire country. (back)

6. Given as Te Aongawa in some whakapapa. (back)

7. Okeroa Pitman descends from Tahora. (back)

8. Te Kupenga and Takarangi were the children of Tuhekeheke of Ngāti Pāoa. (back)

9. Patuharakeke is the hapū whose base is the Takahiwai, Marsden Point and Ruakaka areas on the southern side of the Whangarei Harbour. The administrator is also of close Patuharakeke descent and connection through his paternal grandfather, Okeroa Pitman. (back)

10. Takahiwai is another family marae and wahi tapu where the administrator’s grandfather (Okeroa Pitman) and father (Manira Pitman) are buried. (back)

11. Quoted by Nancy Pickmere whose source was another of the administrator’s whanaunga, Iritana Rangikaramea Randall of Otaika. The veracity of this is not clear. (back)

12. Whakaariki was mentioned by Colenso as living at Takahiwai in 1839, described as an old man. Given that at this time Patuone was 75, the term is somewhat relative. (back)

13. There is another Koukou from Ngāti Rua who was killed in battle at the assault on Otuihi Pā in 1837 together with the Waima chiefs Pi, Te Nana and others. Koukou’s head was subsequently preserved, taken to London with that of Moetarau of Ngāti Ngiro and later repatriated to Aotearoa. In the course of this battle which involved Kawiti and Pomare, Patuone in attempting to stop the bloodshed between close kin, called out to Kawiti to cease the assault. The call was immediately heeded. (back)

14. The administrator’s grandfather Okeroa Pitman begain married life at Omaha in the Mahurangi on land from Tauwhitu and Ani. What is very clear here are the multiple connections of Okeroa through his grandfather Tauwhitu to Te Roroa and Te Parawhau as well as to Patuharakeke. (back)

15. Taurau was probably either Paki Taurau or Hona Taurau, both indicated as contributors. (back)

16. 4WH 132 5th December 1894. (back)

17. Refer to tātai provided earlier. (back)

18. Ani Kaaro, a younger sister of the administrator’s grandmother Hoana, was to live out her final days in a small house, set apart at Whakapara. Ani Kaaro and her husband Ngakete Hapeta had no issue. Many years ago, the administrator was told that, amongst other spiritual responsibilities, Ani Kaaro was guardian of a large slab of pounamu, effectively the major family taonga of a material nature. This pounamu was kept under Ani Kaaro’s bed and upon her death in 1923, removed at night by pack horse to a secret location under a giant Puriri tree at Whakapara. In 1962, in the middle of a field in the general location of the hidden block, the administrator tripped over a piece of pounamu which had been broken from the large block by forces unknown and laid mysteriously upon the fresh grass. Kaumātua in the family interpreted this as a tohu, a sign that special recognition and responsibilities had been accorded to the administrator by tūpuna. Subsequently the piece of pounamu vanished mysteriously once more, probably to return to its parent, its Matua Pounamu. Because of the highly tapu nature of this pounamu, it is thought that it is best left undisturbed. The name of the pounamu is itself a dire warning and will not be printed. (back)

19. During all the time the administrator spent with Okeroa and other kaumātua, Ani Kaaro was never discussed in detail: her name was mentioned only in connection with tātai. Another explanation which the administrator also believes to be true is that Ani Kaaro was seen by some in the family to be a personification or reincarnation of Ripia’s stillborn child Te Tuhi and it was her job to put this troublesome presence within the Ripia and Tapua family, finally to rest by setting it up as a benign spiritual kaitiaki for all of Patuone’s descendants. In Māori terms also within these matters of spirituality, time and reason combine in fluidity: when the time is ‘right’ a pre-determined event will occur. Although during the administrator's childhood, there was friendly contact between the descendants of Hoana and Te Tawaka (and also, remembering the fact that there were various tomo between between them), there was much left unsaid. One of the forces operating within the family arose from Te Tawaka's husband, Eru Nehua, who had an infamous reputation for many reasons which are best left unspoken. (back)