Home | Key Dates | Patuone - A Life | Whakapapa | Publications | Photographs & Paintings | Links | Glossary | Contact Us

[Page 1] | Page 2

Whakapapa

Whakapapa or tātai are genealogies and carry great mana for all Māori. It is requested that all users treat these with the greatest respect for in many cases they are made available here for the very first time to a wider audience. Many of these tātai have been handed down to the site administrator as part of oral family history and some were also recorded in the period of the 1880s-1890s in a series of manuscript books along with other historical narratives. All of the old lines of tātai conclude with the administrator's grandmother, Hoana Hohaia. Hoana's brothers and sisters clearly had their own tātai and their uri are responsible for completing and maintaining their own lines. Generally, Māori people do not share tātai with persons who are not related to the tūpuna named. An exception is made in this case to facilitate access for many Patuone uri all around the world. All descendants are welcome to provide updating tātai which complete more contemporary linkages and lines of descent. These should be addressed to the site administrator in the first instance. All contributors with be listed to acknowledge contributions. (Note: the term tātai is used much more in Ngāpuhi than whakapapa. When the administrator was growing up, kaumātua never used anything but tātai when speaking about genealogies. On this site, however, both terms are used interchangeably).

Please Note: These tātai are a work in progress. As additional information is provided to augment that already known by the administrator, this section will be updated and re-ordered. Please feel free to contact us with your additions and corrections. All the old tātai can also be added to as more information emerges. With generations following that of the children of Hohaia and Kateao Te Takupu, these are in more recent memory and generally, can be supported by known birth and death dates and official documents such as birth and death records. There are also detailed family records held by descendants all over the world. If those who hold such records are happy to share, these can be put up on the site and all uri of Patuone can see how they link up. There are some, however, who do not feel comfortable with this. This is their decision. The many linkages are extensive and endlessly fascinating, especially with tomo arrangements which occurred up to the administrator's father, Manira's, generation. There are also, however, records held which are not correct. By putting up all records and pointing out where the facts are not clear or remain to be corroborated, we are all able to share in a collective building role. Some family members prefer that their details should not be placed here for public access. They can therefore look after their own.

There is some disagreement about birth dates and order for Patuone's grandchildren and there are some descendants who place great emphasis on claiming the tuakana or mātāmua line, the so-called senior line. The senior line is merely a quirk of birth: the true line of power is the mana line and this is something descendants cannot claim. Mana is awarded by the tūpuna.

In relation to the birth dates for Patuone's grandchildren, some descendants claim specific years when there are no actual records. Māori births were not routinely recorded in the manner of European births until 1913. Also, much information related to birth years, recorded on tombstones and memorials is simply incorrect, resulting from imperfect memories, guesses and approximations. The administrator believes that his grandmother, Hoana Hohaia, was born c.1863. Her last child (the administrator's father, Manira) was born on 9 December 1911. Thus, assuming that Hoana was at the end of child-bearing days in 1911, this would give her an approximate age of 48 and on her death in 1935, an age of 72. Given that she was the third born of Hohaia and Kateao Te Takupu's children, although others claim birth years for older sister Te Tawaka as 1845 and younger sister Ani Kaaro as 1848, the administrator believes these claims are far too early. The matter is complicated by the fact that although it is believed that Hohaia was born c.1825, other sources suggest 1835. A more likely scenario is that Patuone Hohaia and Te Tawaka Hohaia were born in the late 1850s. Ani Kaaro is also decribed in the early 1900s as being about 40. A more likely year for her birth is c.1865 with the remaining siblings thereafter. If more concrete evidence can be produced, these details will, of course, be updated.

Ngāti Hao The Hapū

This has been covered in the respective sections on Ngāti Hao and Ngāpuhi and will not be repeated here.

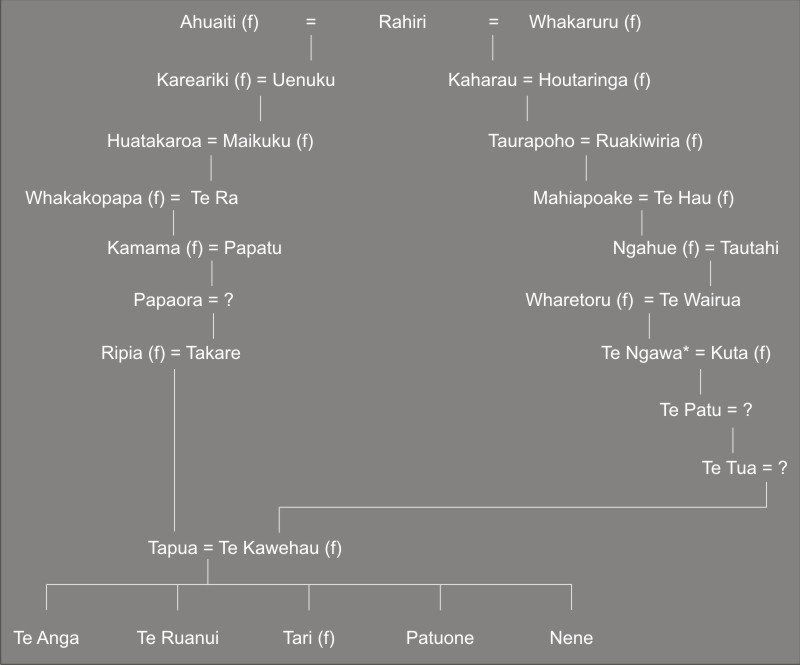

As indicated, Tapua, the father of Patuone and Nene traced descent direct from Uenuku, the first-born son of Rahiri and his first wife Ahuaiti. Ngāti Kahu is also significant in Tapua's tātai. Apart from the Hokianga origins, Tapua’s established base was the Kerikeri inlet where he had a pa at Ōkura, a tidal reach of the inlet backing onto Waitangi. Te Kawehau, mother of Patuone and Nene traced descent from Rahiri through Kaharau, his second son from the union with Whakaruru. The basic whakapapa is:

DESCENT OF PATUONE

* Te Ngawa appears in some tātai as Te Ngaua. Spelling variations may occur with other names also, Maui and Mawi, for example.

The point has been made in many sources about the importance within Ngāpuhi of descent from Rahiri who was born within the period 1475-1525. The various family tātai cited here show how Patuone’s descent comes through multiple lines from both Uenuku and Kaharau, respectively first and second born sons. These multiple tātai also show clearly the close kinship of all the famous rangatira of Ngāpuhi.

The reason for Rahiri’s pre-eminence probably relates more to his standing as eponymous ancestor and linkages to preceding tūpuna rather that for any great military prowess. It was Kaharau in particular who founded the military might of Ngāpuhi and together with his older half-brother Uenuku, created a dynasty of famous chiefs and what was to become the largest iwi confederation in New Zealand.

The administrator’s collection of archives includes considerable detail in relation to the Whakanekeneke Block located in the hills above Waihou Valley. The shares in Whakanekeneke were finally partitioned in 1915 and divided amongst Hohaia's children, Eru Patuone Hohaia, Te Tawaka Hohaia, Hoana Hohaia, Ani Kaaro Hohaia, Kaioha Hohaia, Raupia Hohaia and Raunatiri Hohaia, as a result of a decision within the Native Land Court. Subsequently, various Whakanekeneke sub-blocks were to figure in various deals related to the taking of land for public works, notably the main north railway.

The final partitioning was subject to two decisions and subsequent orders within the Māori Land Court dated 29 September 1914. There had been original examinations within the then Native Land Court and Appellate Court in 1899 and 1900 respectively and a further Court consideration of matters in 1908. At stake was considerable disputation between Ani Kaaro and Te Tawaka on the one hand and the rest of their brothers and sisters on the other, over the way in which shares in the eight parts of the Whakanekeneke Block had been divided up by Hohaia. Both Te Tawaka and Ani Kaaro had been allocated more shares by Hohaia, with an added complication that Hohaia had also allocated shares to Ani Kaaro's husband, Ngakete Hapeta. In the view of Hohaia and Ani Kaaro, Ngakete's descent within Ngāti Hao entitled him to shares. Another issue was that Hohaia had allocated shares but stood himself outside of the allocation, meaning that the Court then had to decide on how his shares would be distributed. In the event, shares were allocated to Ngakete in the final decision and also to his brothers and uncle and various other members of Ngāti Hao in addition to the Hohaia children. However, although it was decided that Ani Kaaro should receive more shares for the fact of her having maintained ahi kaa over the years and also that Te Tawaka would receive more shares in accordance with the wishes of Hohaia, the matter created great division within the family. The other siblings clearly felt that they had been unfairly treated by their father. It seems obvious from the records and evidence available that Hohaia's decision-making capabilities had been questioned and it may reflect the outcome of some medical condition which affected him prior to his death in 1901. It is also clear that Ani Kaaro had an imperfect knowledge of key tātai, this fact being noted by the Court in the 1914 Judgement. As a fact, it is also interesting. It raises a question about Ani Kaaro's capacities and the possibility that she bullied her siblings for her own ends. As a major force within the family, she may also have engendered certain fears, given an accepted tohunga matakite status.

Of Raunatiri, the teina of the Hohaia family, little is known or recorded in the author’s family archives. Raunatiri married Taati Pairama and from this union came Korowainga. The name Raunatiri is a Māori transcription of an English name ‘Rountree’. In 1953, the author’s father, Manira, for consideration of £120 plus £1 commission, purchased a share of land in Puhipuhi 4B S.1, recorded as belonging to Raunatiri. The official Department of Māori Affairs receipt for the purchase (No.18209) is dated 8th July 1953 and is described as being a “vesting order Puhipuhi 4B S.1 Block”. The vendor is indicated as Korowainga Rowntree. There are, however, many descendants of Raunatiri on the Rountree line including four great-great grandchildren of Patuone. Raunatiri also had a keen sense of the political. Apart from the deep ancestral links between the Patuone family, Ngāpuhi and Tainui through Ngāti Paoa to the Kahui Ariki, which might in part explain Ani Kaaro’s support of the Kingitanga movement, it is interesting to note that younger brother, Raunatiri, was in no way prepared to support any mana outside his own and that of Ngāpuhi. In July 1903, during a visit to the Taranaki area, he wrote a letter to the Fielding Star, which was reprinted in the Hawera and Normanby Star:

I have read in your paper the words of Parata in the House, and of Taiaroa in the Council, about Mahuta. I am a visitor to your district, but would wish to state in your paper, as a descendant of Eru Patuone (my grandfather) and my great uncle (Tamati Waaka Nene) that the words of Parata and Taiaroa are etikaana [e tika ana]. This is to say: Mahuta is only a chief of his tribe, and I, as a Ngāpuhi, scorn the idea of his vaunted kingship. Hawera & Normanby Star, Vol.XLVI, Issue 7739, 13 July 1903, p.2. (Note: the use of the Māori terminology, ‘e tika ana’ (it is true) is an assertion that statements made previously by Parata and Taiaroa are true. Mahuta was the 'Māori King' within the Kingitanga movement in Tainui).

The interesting thing about Raunatiri's comments, along with those of Parata and Taiaroa, is that they reflect an early reaction to any suggestion that the 'Māori King' had any jurisdiction outside of the Tainui confederation. There was also an early understanding in Ngāpuhi that the Kingship role would be shared around and not monopolised forever by Tainui. In the administrator's experience, during the 1950s, kaumātua in Ngāpuhi talked about this a great deal. The view was that the Kingship should have come to Ngāpuhi as part of a cycling and sharing process.

Te Whānau A Tapua – An Illustrious Family

Ko te whaiti a Ripia!

We are the small band of Ripia!

This pepehā (saying) was uttered by Patuone in response to a taunt from his relative Heke, prior to the battle of Okaihau. When Heke saw that the numbers of the Patuone and Nene forces were small, he suggested that they would do better to return to their homes and not risk their lives. In response, Patuone’s pepehā invokes the name of his grandmother, Ripia and is a direct response to the challenge issued by Heke: the clear message was this: we may be few in number but we are strong and valiant in battle. The invocation by Patuone of Ripia is highly significant and provides clear evidence of the powerful mana and high tohunga status of his grandmother.

Apart from Patuone’s older brothers Te Anga and Ruanui who were killed in battle with Ngāti Pou of Whangaroa while in a taua with Tapua, Nene and their sister Tari complete the Tapua family, Tari being the oldest. Another half-brother Wi Waka Turau who died while a comparatively young man, was the son of Te Kawehau by her second husband. Wi Waka Turau, however, was present with Nene and Patuone at a number of fights, including that at Ruapekapeka and was still a key part of the Ngāti Hao leadership.

Tari married the Pēwhairangi chief Te Wharerahi, brother of Rewa and Moka and son of Te Auparo who were of Ngāi Tāwake. Te Auparo was killed in one of the many complex disputes amongst close descent groups, in this case, Te Ngare Raumati and Ngāi Tawake. Her killing in a cultivation of keha (turnips) gave rise to the name Patukeha. Te Karehu, the sister of Te Wharerahi, Rewa and Moka, was taken by the Te Ngare Raumati party and subsequently killed and eaten 1. Like Patuone, Te Wharerahi was a great warrior and renowned peacemaker and thus his marriage to Tari created a significant alliance with Patuone and Nene which also formalised another link between Hokianga and Pēwhairangi 2.

Tapua, the father of Patuone and Nene traced descent direct from Uenuku, the first-born son of Rahiri and his first wife Ahuaiti.

Ko ēnei aku tātai mai i a Patuone.

Ko ēnei o matou tātai mai i a Patuone.

These are my lines of descent from Patuone.

These are our lines of descent from Patuone.

The direct whakapapa taken through to the administrator’s grandmother is:

Rahiri = Ahuaiti (f) (1)

Uenukukuare = Kareariki (f)

Maikuku (f) = Huatakaroa

Te Ra = Whakakopapa (f)

Kamama = Papatu

Papaora =

Ripia (f) = Takare

Tapua = Te Kawehau (f)

Patuone = Te Hoia (f)

Hohaia = Kateao Te Takupu (f)

Hoana Hohaia (f) = Okeroa Pitman

Te Kawehau, mother of Patuone and Nene traced descent directly from Kaharau, the second-born son of Rahiri from his wife Whakaruru. The direct wkakapapa taken through to the administrator’s grandmother is:

Rahiri = Whakaruru (2)

Kaharau = Houtaringa (f)

Taurapoho = Ruakiwhiria (f)

Mahiapoake = Te Hau (f)

Ngahue (f) = Tautahi

Te Wairua = Wharetoru (f)

Te Ngawa = Kuta (f)

Te Patu =

Te Tua =

Te Kawehau (f) = Tapua

Patuone = Te Hoia (f)

Hohaia = Kateao Te Takupu (f)

Hoana Hohaia (f) = Okeroa Pitman

Another line coming down to Te Kawehau from Kaharau illustrates how chiefly bloodlines were managed through often extensive tomo (arranged marriages):

ta Rahiri ko Kaharau

ta Kaharau ko Taurapoho

ta Taurapoho ko Tuwharepapa

ta Tuwharepapa ko Tuwharekakaho

ta Tuwharekakaho ko Te Wharerangi Kokopu

ta Te Wharerangi Kokopu ko Ruangāio

ta Ruangāio ko Te Mumanga

ta Te Mumanga ko Te Kawehau

ta Te Kawehau ko Tari

ko Patuone

ko Nene

Sissons et al offer a different version of this whakapapa in relation to Rahiri. Their version has Tuwharepapa and Tuwharekakaho descending from Ruanui and Nukutawhiti, as the offspring of their respective progeny Korakonuiarua and Moerewa. Thus, their implication is that Tuwharepapa and Tuwharekakaho precede Rahiri. This implies two different people with the same name in later generations 3. Another significant factor in this whakapapa is Ruangāio whose progeny became part of the move of various components of Ngāpuhi towards Whangarei.

Patuone’s grandmother, Ripia appears as one of the many strong women of Ngāpuhi who wielded great power and influence aside their men folk 4. As indicated, Patuone’s reference to her in his pepehā was a direct acknowledgement of her status and power. Given Patuone’s father Tapua’s ranking as rangatira and important role as tohunga it is probable that Ripia also was a powerful tohunga in her own right. Ripia traced descent from another tūpuna called Ruangangana:

ta Ruangangana ko Pohokuo

ta Pohokuo ko Te Kare

ta Te Kare ko Te Whiuwhiu

ta Te Whiuwhiu ko Te Paehangi muri iho ko Pango

ta Pango ko Wharu

ta Wharu ko Ripia

ta Ripia ko Tapua

ta Tapua ko Patuone

ta Patuone ko Hohaia

ta Hohaia ko Hoana

Another line from Maikuku is:

ta Maikuku ko Te Ra

ta Te Ra ko Kamama

ta Kamama ko Ruakino

ta Ruakino ko Maru

ko Papaora

he teina

This differs from other published tātai in that it gives Ruakino—missing from all others—and also indicates that from Ruakino come Maru, Papaora and another sibling simply given as ‘he teina’ (a younger sibling).

The close descent from Rahiri, in common with all the chiefly lines of Ngāpuhi, is further reinforced by the tātai of Patuone’s grandfather, Takare:

ta Rahiri ko Uenuku

ta Uenuku ko Uewhati

ta Uewhati ko Te Rarau

ta Te Rarau ko Te Ahitaki

ta Te Ahitaki ko Matakiri

ta Matakiri ko Te Rahoo

ta Te Rahoo ko Takare

ta Takare ko Tapua

ta Tapua ko Patuone

ta Patuone ko Hohaia

ta Hohaia ko Hoana

Yet other tātai provide further details about close descent and kinship: these relate to Patuone’s mother, Te Kawehau and provide further connections back to Kaharau:

ta Rahiri ko Kaharau

ta Kaharau ko Taurapoho

ta Taurapoho ko Tupoto

ta Tupoto ko Tuiti

ta Tuiti ko Tutahua

ta Tutahua ko Wharetoru

ta Wharetoru ko Te Kuta

ta Te Kuta ko Te Patu

ta Te Patu ko Te Tua

ta Te Tua ko Te Kawehau

ta Te Kawehau ko Patuone

ta Patuone ko Hohaia

ta Hohaia ko Hoana

A further line to Te Kawehau comes down from Ranginui and includes the tūpuna Tautahi, from whom Ngāti Tautahi derive their name:

ta Ranginui ko Patari

ta Patari ko Matariki

ta Matariki ko Te Haua

ta Te Haua ko Te Ruapaenoa

ta Te Ruapaenoa ko Tautahi

ta Tautahi ko Tutehe

ta Tutehe ko Rewatu

ta Rewatu ko Ngawa

ta Ngawa ko Te Patu

ta Te Patu ko Te Tua

ta Te Tua ko Te Kawehau

ta Te Kawehau ko Patuone

ta Hohaia ko Hoana

ta Hoana ana tamariki

Hohaia, Patuone's son from Te Hoia, married Kateao Te Takupu. Kateao’s tātai shows another strong link with the Hongi line back to Kaharau and Rahiri: Te Hotete is also the father of Hongi. It is clear, however, that Takupu and Hongi could only have been half brothers and that Takupu’s mother was other than Hongi’s. It is known that Te Hotete had at least five wives:

ta Rahiri ko Kaharau

ta Kaharau ko Taurapoho

ta Taurapoho ko Mahia

ta Mahia ko Ngahue

ta Ngahue ko Te Wairua

ta Te Wairua ko Auwha

ta Auwha ko Te Hotete

ta Te Hotete ko Takupu

ta Takupu ko Kateao Te Takupu

ta Kateao Te Takupu ko Hoana

Kateao Te Takupu was the connection through whom the extensive lands at Whakapara, Puhipuhi and Waiotu came to the children of her marriage to Hohaia. Kateao connected to Ngāti Hau and Ngāti Wai who are closely related.

A related tātai shows additional linkages related to this, ending with Hongi’s son Hare Hongi and daughter, Harata Rongo who married Heke:

Rahiri = Whakaruru (f)

Kaharau =

Taurapoho =

Mahia = Hauangiangi (f)

Ngahue (f) = Tautahi

Te Wairua = Waikainga (f)

Auwha =

Te Hotete = Tuhikura (f)

Hongi = Turikatuku (f)

= Hare Hongi

= Harata Rongo (f) = Heke

In turn, Hongi’s senior wife Turikatuku, in keeping with the purity of lines from Rahiri has the following descent, which shares common linkages with another branch from Ngāpuhi to Tainui through the Torongare line but branches off at Te Rongopatutaonga:

Rahiri = Whakaruru (f)

Uenuku

Maikuku

Torongare

Te Rongopatutaonga

Te Aokarere

Kohine

Nehe

Te Mutunga

Turikatuku

These old whakapapa show some more extensive linkages to other significant tūpuna of Ngāti Kahu and relate to Patuone’s second wife, Te Hoia. . Tapua, father of Patuone also had connections to Ngāti Kahu:

ta Te Mamangi ko Rangihi

ta Rangihi ko Hau

ta Hau ko Tu

ta Tu ko Tatai

ta Tatai ko Tao

ta Tao ko Tumataroia

ta Tumataroia ko Te Iwa

ta Te Iwa ko Teretai

ta Teretai ko Paparangi

ta Paparangi ko Te Makaka

ta Te Makaka ko Te Papanui

ko Maui

ta Te Papanui ko Kanohi

ta Kanohi ko Huha

ta Huha ko Tuwharerangi

ta Tuwharerangi ko Tama

ta Tama ko Te Hoe

ta Te Hoe ko Te Waihaha

ta Te Waihaha ko Puke

ta Puke ko Tarakihi

ta Tarakihi ko Te Hoia

ta Te Hoia ko Hohaia

ta Hohaia ko Hoana

kati tenei

Papanui’s sibling Maui has the following descendants:

ta Maui ko Mahuru

ta Mahuru ko Waipariki

ta Waipariki ko Te Mihinga

ta Te Mihinga ko Waimatarangi

ta Waimatarangi ko Te Ripanga

ko Te Ripanga ko Ngei

ta Ngei ko Te Wheoki ko Te Nao

ta Te Wheoki ko Mane

ta Mane ko Ka

ta Te Nao ko Riria

ta Riria ko Pepi

ta Pepi ko Te Paea

kati tenei

Te Hoia, Patuone’s second wife, was mother of Hohaia. Her tātai includes descent from another tūpuna, Mirukaiwha and also includes the tupuna Tohia who was regarded as a significant Ngāti Hao tupuna:

ta Mirukaiwha ko Tamakuare

ta Tamakuare ko Rongomaitekawa

ta Rongomaitekawa ko Rakumea

ta Rakumea ko Kurairorohea

ta Kurairorohea ko Korohaere

ta Korohaere ko Te Maunga

ta Te Maunga ko Urutakina

ta Urutakina ko Tohia

ta Tohia ko Panoko

ta Panoko ko Kopu

ta Kopu ko Mano

ta Mano ko Moenga

ta Moenga ko Te Hoia

ta Te Hoia ko Hohaia

ta Hohaia ko Hoana

kati tenei

and in a clarification of parentage:

ta Te Nga ko Moenga

ta Moenga ko Te Hoia

ta Te Hoia ko Hohaia

While these whakapapa from Tama relate to the above, they also link to Te Kawehau, Patuone’s mother:

ta Tama ko Horomanga

ta Horomanga ko Te Tawhinga

ta Te Tawhinga ko Te Kerekere

ta Te Kerekere ko Irikohe

ta Irikohe ko Tokowha

ta Tokowha ko Tatauaraia

ko Te Tua

ta Te Tua ko Te Kawehau

ta Te Kawehau ko Patuone

ta Patuone ko Hohaia

ta Hohaia ko Hoana

Apart from the fact that these tātai have never previously been published outside family documentation, they illustrate some important features worthy of comment. As tātai, they were intended to be recited, indicated by the use of ta and ko, effectively meaning in context, from and came. Kati tenei or whakamutunga indicate the conclusion of a line 5.

The maintenance of close and tight bloodlines was a particular feature of the Māori aristocracy and these tātai illustrate the point very clearly. As much as Ngāpuhi diversified through external marriage, they also maintained these close descent lines from Rahiri, Uenuku and Kaharau through the inter-marriage of cousins and other kin. In this way, Ngāpuhi tuturu lines were maintained with fullest integrity.

As indicated previously, another important matter in relation to tātai, at least for some, is to work out when certain tūpuna lived. Teachings given to the administrator indicated that these details are really insignificant: tūpuna are tūpuna regardless of all other details. Specific dates are really only relevant in attempting to establish rights of occupation to certain places. However, for those whose interests are in dating specific people, one method used is to count back, allowing twenty five years to thirty years per generation to arrive at an approximate date.

Patuone’s grandmother Ripia also figures prominently in the oral history related to the family and provides another link with the spiritual inheritance and legacy of Patuone. Ripia had a stillborn child called Te Tuhi, in old Māori terms, this being a major tohu. Thereafter, this child would visit his living kin in the form of a kehua, an apparition, and it was a clear intention that Patuone should become the medium of connection between the worlds of the living and the dead. This, however, Patuone resisted. While there exists no explanation about the particular circumstances of and motives for this resistance on the part of Patuone, it probably relates to his fulfilling predictions made about him at his birth and also a rejection of the darker side of the priestly arts 6.

Another interpretation is that Te Tuhi was a trickster in the tradition of Maui. Also Tai Tokerau is regarded by Māori from other iwi as being somewhere to avoid being alone after dark unless in the company of tangatawhenua: kaumātua from other iwi have suggested that this is because of the pathways to Te Reinga and closeness of Te Reinga itself 7.

Reference to various family tātai dating from the 1880s show how many tūpuna link up, adding the human dimension to various events and migrations. As is typical, these linkages are extremely complex and extensive and take a lot of working through as they do not necessarily show complete connections and in fact, some may directly contradict others. Indeed, the tātai related to the Whangarei whanui area illustrate very well some of the challenges discussed earlier in basing and constructing a clear history on the details and ‘evidence’ of whakapapa alone especially in relation to orthography, the repetition of names over different generations and multiple marriages.

Apart from the fact that Ahuaiti, Rahiri’s first wife and mother of Uenuku was from Ngāi Tāhuhu and Ngāti Manu, another Whangarei area connection back to Ngāpuhi tuturu and Rahiri came through the Ruangāio line from Kaharau.

In the tātai related to Whangarei, one key rangatira to emerge is Kūkupa, father of Tirarau. Kūkupa was born c.1775 at Taurangakotuku, located on the northern bank of the Otaika River and near Toetoe, overlooking the Whangarei Harbour 8.

Another name which appears in tātai is Motatau, however, for all the expectation provided by the name and its association with a significant place for Ngāti Hine, he does not emerge as a prominent figure at all in terms of recorded or oral deeds and exploits: apart from his appearing in the tātai and working through various linkages, there is little archival or oral history detail about him. He does not appear directly in any of the administrator’s Rahiri tātai which cover all the chiefly lines from Rahiri. It is likely that the connections, given the name Motatau, are through tātai more specific to Ngāti Hine or Ngāti Manu. Together with Waiomio and Taumarere, Motatau and Kawakawa are key areas and define the rohe of Ngāti Hine and Ngāti Manu so this bears further exploration. Having said this, however, in the administrator’s tātai, there is still no clear detail. Kawiti’s son, Maihi Paraone Kawiti of Ngāti Hine does appear in one of the tātai groups, as does Hineamaru who is the tūpuna from whom they derive their hapū name. Hineamaru’s Ngāpuhi descent is from Rahiri and Uenuku through the marriage of Torongare and Hauhaua. The following tātai from the administrator’s grandfather Okeroa illustrate the key connections:

Rahiri ka moe ia Ahuaiti

Ko Uenuku ia Kareariki

ko Hauhaua ia Torongare

ko Hineamaru

ko Te Aongaua

ko Tamangana

ko Tamangana ia Rangiheketini

ko Ruangāio ia Te Ika-a-te-Awa

ko Taurahaiti ia Whareangiangi

ko Kauangarua ia Te Haara

ko Karetu ia Mara

tana ko Hotu, ko Matai ko Te Ngorengoreko Hotu ka moe ia Te Pare

ko Rauru ia Waikoraha

ko Meripui ia Wipou

ko Hoana muri ko Weretaata Matai ko Te Paekoraha

muri ko Te Hana muri ko Te Pukohukohu

ta te Paekoraha ko Te Rahiri

tana ko Tawa Te Rahirita Te Hana ko Te Whaa muri ko Te Ahomatau

ta Te Whaa ko Paora Kerei me etahi atu

ta Te Ahomatau ko Te Huka

tana ko Hemi Te Huka

ta Te Pukohukohu ko Hare ko Te Hounui ko Te Okuoku

ta Hare ko Wheoro ko Te Uriheke

ta Wheoro ko Tiwe

ta Te Uriheke ko Te Koni ko Ngawiri

ta Hounui ko Heneriata

ta Te Okuoku Marara Ngātirua

ta Te Ngorengore ko Te Pouwhare

tana ko Te Wera muri ko Te Ahiterenga muri ko Nihi muri ko Te Arahi

ta Wera ko Ewa tana ko Te Patene

whakamutungata Te Ahiterenga ko Ani tana ko Tokitahi

ta Nihi ko Perepe Nihi

ta Te Arahi ko Aterea Te Arahita Te Kauangarua ano

ko Hautakare tana

ko Tumu ko Tuwhakatere ko Taratara

ta Tuwhakatere ko Whitiao

ko Taupaki ko Te Hauauru

moe katoa enei wahine ia Kūkupata Whitiao ko Te Ipuwhakatara muri ko Koke

ta Ipuwhakatara ko Tito

tana ko Huirua ko Te Kawenata me tahi atuta Koke ko te Roma ko te Ngere ko Te Ruu

ta Te Roma ko Kake ko Himi

ta Kake ko Nua Kake me tahi atu

ta Himi ko Onepu Himi

ta Te Ngere ko Henare Panoho

ta Te Ruu ko Hori Tarawau

ta Taupaki ko Tāwera muri ko Wipou muri ko Tamaroa muri ko Taurau

ta Te Wera ko Waata Te Ahu

tana ko Te Pouritanga muri iho ko Pouaka W. Paroreta Wipou ko Hoana ko Were

ta Hoana ko Haora me tahi atu

ta Were ko Erana me etahi atu

ta Tamarao ko Eru Moare

tana ko Pute tana ko Meretiawa

kahore he uri o Taurauta Te Hauauru ko Te Matengahere

raua ko Tiakiririta Te Matengahere ko Kerenapu tana Wiremu Te Hau muri ko Hiraina

ta Tiakiriri ko Kiriwera muri ko Te Rata Koro muri ko Te Toko muri ko Te Wana muri ko Te Waikohua

ta Kiriwera ko Te Rata Rimi tana ko Tapa ka moe ia Te Ihi Titota Te Rata Koro ko Te Keepa ko Peka ka moe ia Tamehonihana

ta Te Toko ko Winika ka moe ia Te Reweti Paenganui

ta Te Wana ko Powahia ka moe ia Te Keha Wikamo

ta Te Waikohua ko Papara

ta Taratara ko Kawa tana ko Maihi P. Kawiti

ko Kokako ka moe ia Ruatangihia

putamai ko Tuta muri ko Neheta Tuta ko Te Kotahi tana ko Te Porohau tana ko Taotaoriri tana ko A. Whareumu tana P.A. Whareumu

ko Te Haupai

Specifically to Nehe and Motatau the tātai are:

ta Nehe ko Motatau ka moe ia Te Kamo ko Te Taotahi ia Te Ao-Hei-Awa puta ko Nehe muri ko Te Whakariki muri ko Te Korehu muri ko Te Oneho

ka moe a Nehe ia Te Tiatana puta mai ko Te Amoteriri

ka moe ia a Te Whakaariki ia Te Poho

puta mai ko Te Korehu muri ko Te Pirihita Te Korehu ko Purangi

ta Te Pirihi ko Wiki Te Pirihi

ka moe a Te Korehu ka moe ia Te Ruu puta mai ko Ripeka Tuapaka muri ko Rangiripo ka moe ia Paora Kerei puta mai ko Ngakapa

ka moe a Te Oneho ia Te Tatua puta ko Hori Wehiwehi

ka moe a Ripeka Tuapaka ia Tipene Haare puta ko Wairakau ia Te Hikoi

ta Nehe ano ko Pukerahi tana ko Te Rou tana ko Te Paeamoe tana ko Mohi muri ko Taparoto ta Mohi ko Reti Mohi ta Taparoto ko Tari Keha

The significance of these tātai is that collectively, they indicate wide linkages throughout much of Tai Tokerau. In the above tātai, for example, Te Tatua is mentioned, together with his wife, Te Oneho. Te Tatua was a rangatira of Ngāti Wai and Ngāti Toki and his people lived on Tawhitinui (The Poor Knights Islands) off the coast and north of Whangarei. The two islands which make up Tawhitinui are Tawhitirahi and Aorangi. In 1820 when Te Tatua was away fighting with Hongi, the rangatira Waikato of Te Hikutu in the Hokianga, attacked Tawhitinui and decimated the population. Te Tatau had allegedly insulted Waikato and the latter, having been advised by an escaped slave that the islands were largely undefended, decided to seek utu for the insult. Tawhitinui was abandoned after this although Te Tatua’s wife Oneho and son Hori Wehiwehi both survived the Te Hikutu raid. Te Oneho and her daughter were taken as hostages by Te Hikutu, however, were recognised as relatives by a local rangatira during a stop at Whangaroa. This rangatira helped them escape. In fact, Oneho was a direct descendant of the rangatira Nehe, through Motatau and Te Kamo. She was a daughter of Te Taotahi and Te Ao-Hei-Awa.

Significantly also, many of these old tātai indicate rangatira who are often not mentioned in any other tātai or historical accounts. This again indicates the importance of the family records maintained by the site administrator. In some accounts, Tawhitinui is confused with Tawatawhiti which is the peninsula stretching to the Whangarei Heads from Parahaki.

Motatau and Te Kamo’s son Te Taotahi was born c.1750. It is likely that Motatau and his people were part of the general drift southwards, whether their connection was partially through Ngāti Ruangāio or elsewhere. It would be reasonably expected, however, that if this were the case, more extensive detail of them would be recorded in whakapapa. Ruangāio is in the Rahiri line as are many others who became associated by name with specific hapū. The administrator’s tātai suggest that Motatau was a grandson of the union of Kokako and Ruatangihia and that their son Nehe was his father 9. Part of the old and extensive whakapapa in the administrator’s possession provides evidence although this is further complicated by multiple marriages, particularly in the case of whakapapa relevant to the Whangarei area and especially to Te Parawhau 10, Patuharakeke and other hapū and iwi groupings linked through inter-marriage:

Ko Kokako ka moe ia Ruatangihia

putamai ko Tuta muri ko Nehe

ta Nehe ko Motatau ka moe ia Te Kamo

ko Te Taotahi ia Te Ao-Hei-Awa puta ko Nehe2nd muri ko Te Whakaariki muri ko Te Korehu muri ko Te Onehoka moe a Nehe2nd ia Te Tiatana puta mai ko Te Amoteriri

ka moe ia a Te Whakaariki ia

Te Poho puta mai ko Te Korehu muri ko Te Pirihi

ta Te Korehu ko Purangita Te Pirihi ko Wiki Te Pirihi

ka moe a Te Korehu ka moe ia Te Ruu puta mai ko Ripeka Tuapaka muri ko Rangiripo ka moe ia Paora Kerei puta mai ko Ngakapaka moe a Te Oneho ia Te Tatua puta ko Hori Wehiwehi

ka moe a Ripeka Tuapaka ia Tipene Haare puta ko Wairakau ia Te Hikoi

ta Nehe2nd ano ko Pukerahi tana ko Te Rou tana ko Te Paeamoe tana ko Mohi muri ko Taparoto ta Mohi ko Reti Mohi ta Taparoto ko Tari Keha

Other tātai of use here are traced from Taurahaiti and show:

Taurahaiti

tana Tawhiro

tana Tokaitāwhio

tana ko Kūkupa

tana Tiakiriri

tana WaikohuaTaurahaiti

tana ko Te Raki

tana ko Urekuri

tana ko Te Poho

tana ko Te Pirihi

tana ko Wiki Te Pirihi

tana ko Maki PirihiNote: The name 'Urekuri' is certainly written as such in the administrator's tātai. It is possible, given the meaning of the word and name that it should be 'Urikuri' instead. (Ure = penis; kuri = dog). Uri = descendants; Kuri = the name of an ancestor). This may well be a reference to ancestry from Ngāti Kuri, an iwi grouping in the far north of Tai Tokerau.

DESCENT FROM PATUONE AND TE HOIA

THE CHILDREN OF HOHAIA, SON OF PATUONE

There are extensive issue from all these children from the marriage of Hohaia and Kateao Te Takupu and over the years. continuing a long tradition, there were many tomo arrangements.

While many of these connections are known, due to the sensitivities of certain descendants, no further details will be provided for public access. It is also up to various descendants to record their own details, particularly relating to descent thereafter.

DESCENT OF HONGI

RECENT SUGGESTED CONNECTIONS

Since the launch of the website, the administrator has received many emails in relation to descent from Patuone. One from informant Gray Keyworth draws attention to what is suggested is a further link to Patuone through his second wife, Te Hoia, who was the mother of Hohaia. This marriage, it is known, produced three (3) sons and one (1) daughter, the names of whom, apart from Hohaia, are not recorded in the administrator's official whakapapa. Gray Keyworth suggests that the name of Hohaia's sister is Hapi Waka and that the descent is:

Patuone = Te Hoia (f)

ko Hohaia

ko Hapi Waka (f)

ka moe a Hapi Waka ia Horace Earle Hanley

ko Sarah

ko Henry

ko Hannah

ko Mary

ko Thomas

ko Ellenka moe a Mary ia Henry Stephenson

ko Ida

ko Ellen

ko Henry

ko Charles

ko Mildred

ko Lionel

ko Gladyska moe a Ida ia William Carter

ko Bernice

ko Maisie

ko Beryl

ko Wilfred

ko Joyce

ko Grieta

ko Athene

ko Lionelka moe a Bernice ia Charles Barron

ko William

ko Mollieka moe a Mollie ia Cedric Keyworth

ko Robyn

ko Tony

ko Ross

ko Bruce

ko Gray

Gray Keyworth suggests that Mary and Henry Stephenson lived for a time in Pompallier House at Russell. Henry was of mixed descent with roots back to Te Kapotai.

There is also another Waka connection of interest which appears to bear some relationship with Hapi Waka. A June 1869 reference in the ‘Daily Southern Cross’, provides some interesting details in reporting the capsize of a boat in a squall while en route from Kerikeri to Kororareka with a load of Kauri gum. The article refers to one, Hone Pane, also known as Hone Waka, and indicated as being a grandson of Patuone and grand nephew of Tamati Waka Nene, who drowned in the accident:

He was a young man of very good reputation, and he was greatly respected by both Europeans and natives. His death will be a great blow to our friend, Tamati Waka, by whom he was greatly beloved, and whose position he would have filled at the old chief’s death. (Daily Southern Cross, Vol. XXV, Issue 3712, 11 June 1869, p.4).

Another person drowned in the accident is referred to as a brother-in-law of Hone Waka. These details offer a number of potential explanations, including that Hone Waka was the son of another sibling of Hohaia and Hapi Waka or that Hapi Waka was married prior to her marriage to Horace Hanley, Hone being her son. The suggestion of Hone Waka being Nene’s heir-apparent, is also an interesting detail. The name Waka, certainly suggests a connection with Nene. Hone Waka also captained the “North Shore” a schooner of 19 tons, owned by Patuone, this vessel having been purchased by Patuone for £290. It carried goods and passengers between the Bay of Islands and Auckland and points between.

Part of the value of a site such as this is that it brings out details which can then be further developed and corroborated.

Whakapapa continued [Page 2] >>

_______________________________

1. Te Karehu is an interesting name. A woman of the same name is mentioned in the family accounts of the Hokianga and Mangamuka settler Christopher Harris as being one of his wives. While there is the suggestion in the Harris papers of this Te Karehu having a connection to Tari, Te Wharerahi, Nene and Patuone, the fact is that this is not the same Te Karehu. The Te Karehu killed in this account was merely a girl when she was killed. Williams mentions Christopher Harris coming to call with his ‘young wife’ and this is probably the other Te Karehu referred to in the Harris papers. As part of the utu for the killing of Auparo, a number of chiefs who were involved and deemed responsible, including Tawheta and Tauwhitu, were pursued and killed. The Tauwhitu of these accounts is, however, not the Tauwhitu of the Mahurangi and Whangarei areas who is the great-grandfather of the site administrator though his grandfather Okeroa Pitman. Following the killing of Auparo (who was killed in her turnip (keha) garden), her hapū assumed the name Patukeha as a poignant reminder of her killing. (back)

2. Tari and Te Wharerahi’s children were Tupanapana, Tarapata and Te Tane. In turn, from Tupanapana descended Ina Te Papatahi, Goldie’s favourite model. Tarapata’s daughter, Harata was another preferred model of Goldie. Harata’s brother was Wi Pani. (back)

3. Table 23, p.60 in Sissons et al. (back)

4. High-ranking Ngāpuhi women often accompanied their menfolk to battle to give support and rally the toa with various physical assistance and exhortations. Famously, Hongi’s wife Turikatuku who was blind, did so on many occasions. The fact that Hongi’s sister Waitapu was killed at Moremonui in 1807 as part of a major defeat of Ngāpuhi by Ngāti Whātua and Te Roroa, again illustrates this point. Some senior women were also tohunga in their own right and exerted immense power through the exercise of functions such as matakite. Ani Kaaro, a younger sister of the administrator’s grandmother Hoana was involved in many incidents in the 1880s and events linked to Te Whiti. She was regarded as a prophetess. See Elsmore (1999) in references for more details. (back)

5. There may be subsequent descendants, however, at the time of recording, these tātai were regarded as complete. Tātai which follow in the administrator’s case are recorded elsewhere. (back)

6. Makutu, the imposition of curses upon others were the domain of the tohunga makutu. (back)

7. Te Reinga is the underworld where the dead go following earthly death. (back)

8. Toetoe is also where the administrator’s father was born, this being land linked to Okeroa Pitman through his mother Ani, daughter of the Mahurangi chief Tauwhitu. (back)

9. A second Nehe appears in the relevant tātai related to the first. This second Nehe is clearly female. (back)

10. Te Parawhau derives its name from the death of Tirarau1st who was killed at Punaruku by Rangitukuwaho of Ngāti Wai and Te Waiariki. (back)